Our backyard has been a challenge from the start, which for us was in 2008 when we began building our wildlife garden. The majority of the yard, filled with Bermuda grass, received the full effect of the Death Star (the sun) every day. Every step we took to convert our backyard to a habitat began with the removal of that Bermuda from rock-hard clay soil.

Our backyard has been a challenge from the start, which for us was in 2008 when we began building our wildlife garden. The majority of the yard, filled with Bermuda grass, received the full effect of the Death Star (the sun) every day. Every step we took to convert our backyard to a habitat began with the removal of that Bermuda from rock-hard clay soil.

Our wildlife garden is quite well established now, but we kept putting off tackling the remaining (and still large) “lawn” of Bermuda. The reason simply was the amount of effort involved, but this year I decidedly to make the process simpler by working small areas at a time, seeding them and letting them get established while protecting them from potential encroachment from Bermuda still around.

Area normally in sun — picture taken late in the day. This photo shows the area after it rested under cardboard for several months.

Shovels, cardboard, and time were our tools. In the spring, we dug out a reasonable section of Bermuda completely by hand, taking care to get all the roots. Next, we covered the area with cardboard. Then we waited. I didn’t intend to wait for several months, but that’s what happened, and it worked out for the best. Sometime over the summer, I pulled off the cardboard to let rain soak the ground and see whether any Bermuda would reemerge. Hardly any did, thank goodness.

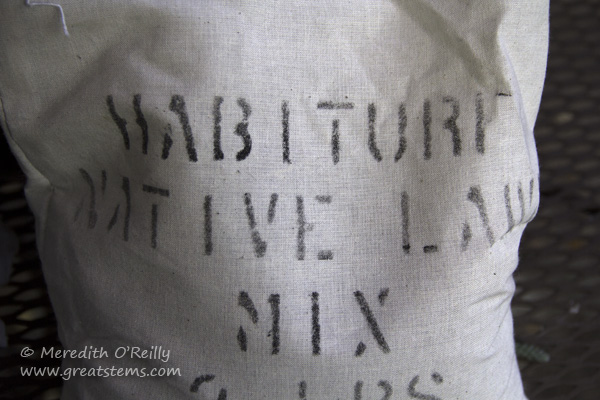

September brought promise of rain for us this year, and it was a fine time to go ahead and seed the Habiturf, a mixture of Buffalo Grass, Curly Mesquite, and Blue Grama seeds. The idea of the three grasses is that diversity of acceptable species has a better chance of crowding out any weeds or Bermuda that might try to establish there, and that diversity helps provide protection from diseases or pests that might otherwise cause problems in a traditional turf lawn.

September brought promise of rain for us this year, and it was a fine time to go ahead and seed the Habiturf, a mixture of Buffalo Grass, Curly Mesquite, and Blue Grama seeds. The idea of the three grasses is that diversity of acceptable species has a better chance of crowding out any weeds or Bermuda that might try to establish there, and that diversity helps provide protection from diseases or pests that might otherwise cause problems in a traditional turf lawn.

First, we used a dirt rake and shovel to loosen up any compacted areas (necessary after months of dogs and people trampled the cardboard and soil).

First, we used a dirt rake and shovel to loosen up any compacted areas (necessary after months of dogs and people trampled the cardboard and soil).

Then we added a light layer of compost and raked it in. The chickens did a better job of mixing it than we did. I highly recommend them as garden helpers and tools.

Then we added a light layer of compost and raked it in. The chickens did a better job of mixing it than we did. I highly recommend them as garden helpers and tools.

They would have particularly loved to find these beneficial rhinoceros beetle grubs that we found in the compost. The grubs were as big as a human thumb — you can see my husband’s thumb in the photo for comparison. But the chickens uncover enough of those grubs in the actual compost bin — the 5 or so we found during the grass process were rescued and delivered to secret places in the yard.

After mixing in the compost and rescuing giant beetle larvae, it was time for the seeds. I sprinkled them by hand — I opted for dense coverage until my husband complained about the cost of the seed. So I lightened up the coverage for the remaining portion. (Guess which section looked the best upon germination? Winner!)

We tamped the seeds into the soil simply by walking on the area. Then I watered thoroughly. The soil had to remain moist for days in order for seeds to germinate — in Texas, this could be the biggest challenge for many would-be native grass gardeners. Fortunately, we had a spell of rain to help.

We tamped the seeds into the soil simply by walking on the area. Then I watered thoroughly. The soil had to remain moist for days in order for seeds to germinate — in Texas, this could be the biggest challenge for many would-be native grass gardeners. Fortunately, we had a spell of rain to help.

To help keep the dogs and chickens out, we created two barriers — one was chicken wire around the border, and I also laid down a sheet of light row cover, both for protection and as a way to help keep the soil moist for longer periods. FYI, the light row cover was more effective than the chicken wire at keeping the chickens out — chickens can both fly over and crawl under things quite easily. Fortunately, they were mostly interested in catching worms that were emerging from the rain, not eating the grass seed or seedlings. Mostly.

To help keep the dogs and chickens out, we created two barriers — one was chicken wire around the border, and I also laid down a sheet of light row cover, both for protection and as a way to help keep the soil moist for longer periods. FYI, the light row cover was more effective than the chicken wire at keeping the chickens out — chickens can both fly over and crawl under things quite easily. Fortunately, they were mostly interested in catching worms that were emerging from the rain, not eating the grass seed or seedlings. Mostly.

Germination was remarkably quick, thank goodness. The plentiful rain helped with that. Once the seedlings were about an inch or so long, I removed the light row cover and stopped worrying about the chickens getting in there. As the grass grows longer and fills in, I’ll share an updated picture.

Germination was remarkably quick, thank goodness. The plentiful rain helped with that. Once the seedlings were about an inch or so long, I removed the light row cover and stopped worrying about the chickens getting in there. As the grass grows longer and fills in, I’ll share an updated picture.

I’m not looking forward to dealing with the rest of the Bermuda, but I feel better knowing the process has begun. It won’t be easy and it won’t be fun, but it will be worth it.

I can’t wait to see what it looks like when it it mature…the length, texture, etc.

I promise to share a picture when it’s bigger, Shawna! I do have an earlier post with a buffalo grass that’s already established: http://www.greatstems.com/2013/05/developing-the-buffalo-grass-patch.html. However, that area I simply threw out seed and it filled in over the years. The problem is that it has numerous weeds, and the rains still let the Bermuda encroach. But I’m still glad it’s there — it will make that section easier to deal with.

Meredith this is wonderful. I have been thinking about native grasses to replace our turf as it is full of weedy plants anyway so you have spurred me to add this to our list.

I wish I’d started it years ago, but the zone of Bermuda was even bigger then. But I know it’s worth it. Getting started is the hardest part!

Yay for grass removal!

Indeed, Katina! I’ll be so happy when it’s all done.