Last weekend I gave my last presentation of the spring, and the very next day I seized an opportunity to work in the garden for a change. It was a beautiful day, and of course in my eagerness to be outside, I forgot both hat and sunscreen, and I soon sported my first and hopefully only sunburn of the year. I wasn’t alone out there, either. Basking in the warmth of the day was this beauty, a male Texas Spiny Lizard (Sceloporus olivaceus).

He was so chubby that at first I thought it must be a female ready to lay eggs, but nope, his markings clearly indicate otherwise. It’s a little hard to see it in this image, but he has light blue stripes along the sides of his belly — females don’t have these.

He wasn’t afraid to let it all hang out, clearly. I’d like to think that if a female were nearby, he suck that chubby belly in, puff out his chest, and do a handsome pose. Clearly he should be practicing those defensive/offensive push-ups male Texas Spiny Lizards are known for (when confronted by other male Texas Spiny Lizards in their territory) — perhaps he could get in better shape. But then again, perhaps this round belly equates to “hot” in the lizard world.

On the other hand, he’s limber enough to do the splits, and to stay in that pose for a while while I took pictures.

Check out the markings on his gorgeous tail.

Yes, yes, you’re a pretty handsome insectivore after all, little big guy.

My son said he saw the lizard coming out of this hole in one of our raised beds. I wonder whether the lizard was using the little tunnel as a cool haven, or whether a female might be prepping to lay eggs in there. I haven’t had a chance to inspect the spot since then to see whether the hole has been covered up or not. If it is, I suspect there might be little eggs inside.

Despite being described as an arboreal species, I have these Texas Spiny Lizards all over my garden and rarely see them on a tree. I guess they have too much to feast on in the garden area. I imagine they’d blend in much better on the bark of a tree than on the wood of my veggie beds or on the rocks around on the pond. But I’m happy they’re willing to hang out on the ground with me.

Getting back to working on the garden, I decided to tackle the weeding of a small perennial patch in the backyard, and in doing so had to move aside several bordering rocks. It’s best to move such rocks carefully — all sorts of little creatures might be sheltering under rocks to stay cool and out of the light (scorpions, centipedes, snakes, etc.), and one wouldn’t want to get a jolt of surprise or worse, pain, from reaching under a rock blindly. But under one rock, I did find a wonderful garden resident.

It was a Tantilla snake, one of the Blackhead species. Some people call them Centipede Snakes, named for their favorite food. The small snakes also eat scorpions and other invertebrates. Like their prey, they are nocturnal and favor rocks to hide underneath. They are colubrid snakes and are non-venomous.

I think this snake must have realized I’m a Snake Whisperer and completely calmed down in my hand. What a beauty. It was probably about 10-12 inches long.

Of course, as soon as I set it down, the snake scurried off for shelter, making use of its fossorial lifestyle and digging right into the earth. But we were able to get a quick picture — you can see the earthy coloration of the rest of the snake’s body.

And so I went back to weeding that garden bed. Lo and behold, under the very next rock was another snake, a much smaller one. It was a Leptotyphlops snake, or a blind snake, about 6 inches long. It looked almost silver in the sunlight but shows a pinkish undertone in the pictures.

These little burrowing, nonvenomous snakes are often confused with earthworms due to their size and coloration. Their eyes are reduced in functionality, serving only to perceive light — they aren’t truly blind, but very nearly so. They spend most of their lives underground.

The main diet of blind snakes consists of ants and termites, along with their eggs, larvae, and pupae. It is believed that the snakes can follow the pheromone trail left by the insects in order to find their colonies. Sometimes blind snakes will also eat millipedes or centipedes. Their scales are smooth and tightly overlap, helping protect the snake from the bites and stings of ants. The tail ends abruptly, mostly rounded with a small point at the very tip.

This little snake was quite a wiggler, and I used a clear bowl with some leaf litter to hold the snake for a moment while I snapped a couple of pictures. But I didn’t want to stress the little snake out — I quickly returned it to the safe haven of its rock in the garden.

I’m so glad to run across these reptiles from to time in my garden. It means my wildlife habitat is functioning well in terms of the ecosystem — predators such as lizards and snakes are natural and very important pest control. Of course at night, they have to be careful, too — we have hungry screech owls that are even higher in the food web, and they’d love a chance to catch one of these little snakes. The lizards, being diurnal, might be safe if they have a good place to hunker down at night. Always excitement in our backyard!

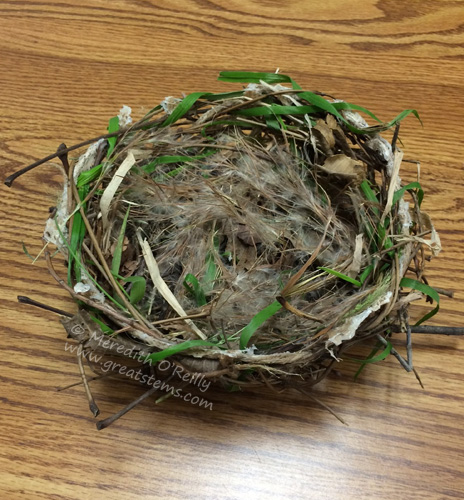

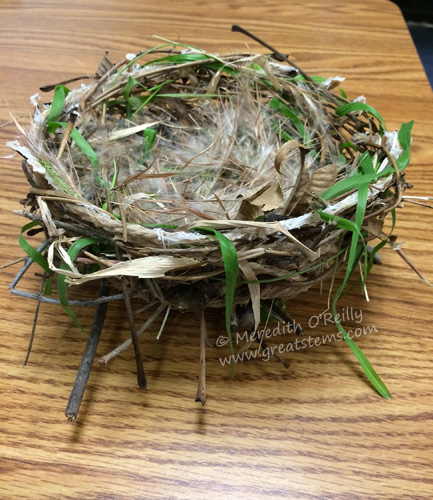

How do you turn this activity in a youth-driven engineering challenge? One option is to have them gather (or you provide) a bunch of natural materials and challenge them to create a basic nest that will hold a set number of like objects, such as 3-4 marbles. They can do so individually or as partners, and it’s a lot of fun. It can also be done in a single lesson or in about a 1-hour time frame.

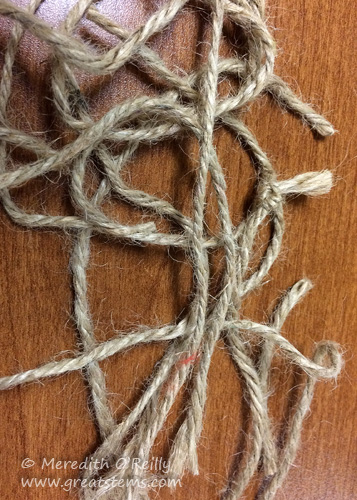

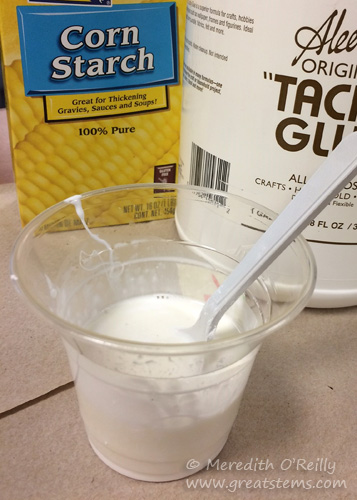

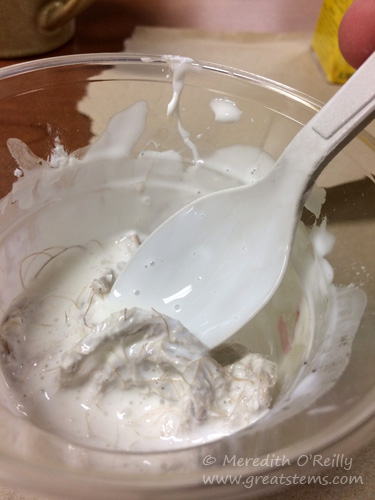

How do you turn this activity in a youth-driven engineering challenge? One option is to have them gather (or you provide) a bunch of natural materials and challenge them to create a basic nest that will hold a set number of like objects, such as 3-4 marbles. They can do so individually or as partners, and it’s a lot of fun. It can also be done in a single lesson or in about a 1-hour time frame. The following shows how to shape the activity using the glue and twine technique. Modify it according to kids’ ideas. Have kids make suggestions for what objects could be used to create a mold for the nest (such as a bowl). Have them also consider how to protect the bowl or other object from the glue (perhaps plastic wrap). Guide kids to see why shorter pieces of twine are potentially safer than really long ones, if the final nest might get placed permanently outside (shorter pieces are safer for wildlife to keep them from getting long twine wrapped around a foot or limb). Have the kids cut the twine into pieces 5-6 inches long.

The following shows how to shape the activity using the glue and twine technique. Modify it according to kids’ ideas. Have kids make suggestions for what objects could be used to create a mold for the nest (such as a bowl). Have them also consider how to protect the bowl or other object from the glue (perhaps plastic wrap). Guide kids to see why shorter pieces of twine are potentially safer than really long ones, if the final nest might get placed permanently outside (shorter pieces are safer for wildlife to keep them from getting long twine wrapped around a foot or limb). Have the kids cut the twine into pieces 5-6 inches long.

Have kids keep adding material until holes and gaps are filled and nothing slips out as they move the nest around. Encourage them to rotate the nest often and triple-check for gaps. To add to the challenge, you could have kids test the strength and stability of the nest by temporarily adding rocks, marbles, or other weighted items, by using a fan to blow on the nest, by giving a gentle shake to the nest, etc. Let kids make adjustments to their nest accordingly. At the end, discuss again how birds in nature make nests and why it’s important for the nest to be sound in structure. Why might different species have different nest-building methods?

Have kids keep adding material until holes and gaps are filled and nothing slips out as they move the nest around. Encourage them to rotate the nest often and triple-check for gaps. To add to the challenge, you could have kids test the strength and stability of the nest by temporarily adding rocks, marbles, or other weighted items, by using a fan to blow on the nest, by giving a gentle shake to the nest, etc. Let kids make adjustments to their nest accordingly. At the end, discuss again how birds in nature make nests and why it’s important for the nest to be sound in structure. Why might different species have different nest-building methods?

While working on the front yard, we ran across this odd creature at the base of a rogue Hackberry seedling. It seemed fairly obvious that it was some sort of caterpillar, until we saw it move. Then it was like… WHOA. Instead of seeing it move along like a regular caterpillar with its legs and prolegs (though apparently a caterpillar actually moves

While working on the front yard, we ran across this odd creature at the base of a rogue Hackberry seedling. It seemed fairly obvious that it was some sort of caterpillar, until we saw it move. Then it was like… WHOA. Instead of seeing it move along like a regular caterpillar with its legs and prolegs (though apparently a caterpillar actually moves  Among its host plants, the Spiny Oak Slug Caterpillar eats the leaves of Oak (no big surprise there), Hackberry (also no surprise), Ash, Cherry, Willow, and many other trees. Though we yanked out the Hackberry seedling — it was growing right in the middle of a multi-trunked Yaupon — we took the caterpillar over to another Hackberry being allowed to grow.

Among its host plants, the Spiny Oak Slug Caterpillar eats the leaves of Oak (no big surprise there), Hackberry (also no surprise), Ash, Cherry, Willow, and many other trees. Though we yanked out the Hackberry seedling — it was growing right in the middle of a multi-trunked Yaupon — we took the caterpillar over to another Hackberry being allowed to grow.

They also seem to share the window a little better than last year’s owlet siblings did.

They also seem to share the window a little better than last year’s owlet siblings did.