In April I had the pleasure of speaking to the Comal Master Gardeners 2012 trainees about wildlife gardening, and it seemed like the perfect opportunity to include a visit to the Lindheimer Home and gardens in New Braunfels.

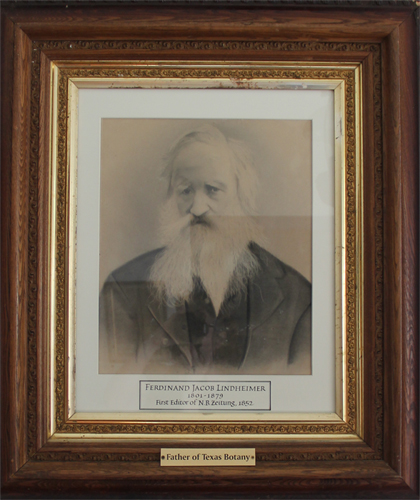

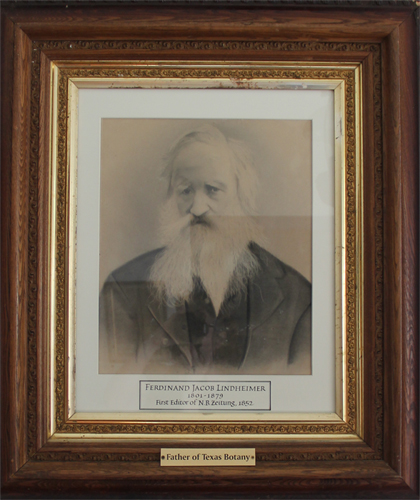

Ferdinand Lindheimer, an extraordinary naturalist and the first permanent-resident botanist of Texas, is particularly notable in part for his vast contributions in the collecting and categorizing of thousands of Texas native plants but also for his unique role in other aspects of Texas history. In fact, his skilled passion for Texas flora earned Lindheimer an honorary title, the “Father of Texas Botany.”

In preparation for writing this article, I drove downtown to the Austin History Center, which includes in its collection of archived books and documents one copy of the translated letters of Lindheimer to renowned botanist George Engelmann, enclosed in the book A Life Among the Texas Flora, by Minetta Altgelt Goyne (note: this is book is still in print and available for purchase). My goal was not to read the entire book that day but merely to get a feel for the passion behind Lindheimer’s plant collecting, as well as to take a closer look at his personal and family history.

Ferdinand Jacob Lindheimer was born on May 21, 1802 (some sources say 1801), in Frankfurt, Germany. Immigrating to the United States in 1834 during a time of political unrest in Germany, Lindheimer traveled first to Illinois and then to Mexico by way of New Orleans. For a short while, he worked on a couple of plantations in Mexico, collecting plants and insects in his spare time. Upon hearing about the Texas Revolution, however, he returned north to enlist in the army, missing the Battle of San Jacinto by a day. After completing his time in the army, Lindheimer farmed for a short while in the Houston area, all the while studying Texas plants and insects.

Ferdinand Jacob Lindheimer was born on May 21, 1802 (some sources say 1801), in Frankfurt, Germany. Immigrating to the United States in 1834 during a time of political unrest in Germany, Lindheimer traveled first to Illinois and then to Mexico by way of New Orleans. For a short while, he worked on a couple of plantations in Mexico, collecting plants and insects in his spare time. Upon hearing about the Texas Revolution, however, he returned north to enlist in the army, missing the Battle of San Jacinto by a day. After completing his time in the army, Lindheimer farmed for a short while in the Houston area, all the while studying Texas plants and insects.

Silk Tassel, named after Lindheimer (Garrya ovata ssp. Lindheimeri), growing wild

Beginning in 1839, Lindheimer spent some time with George Engelmann, botanist at the Missouri Botanical Garden in St. Louis, and Harvard botanist Asa Gray, eventually working out an arrangement to collect and send thousands of Texas floral specimens for categorization. This arrangement would last about nine years. Along with the specimens, Lindheimer wrote long detailed letters to Englemann, and much can be learned about Lindheimer, life and culture in the early settlement of Texas, and Texas’ valuable ecology and geography just by reading the translated letters.

Through Lindheimer’s letters, we learn of his fondness for sweet native grapes and how pecans and persimmons were regular food sources. We learn of different wildlife he encountered, his attention to physical fitness and health, his understanding of local Native American tribes, and just how many species of cacti and yucca there really are in Texas.

Through Lindheimer’s letters, we learn of his fondness for sweet native grapes and how pecans and persimmons were regular food sources. We learn of different wildlife he encountered, his attention to physical fitness and health, his understanding of local Native American tribes, and just how many species of cacti and yucca there really are in Texas.

Often Lindheimer gave detailed accounts of the trials of travel or difficult bouts with illness, and finances were always a necessary topic to discuss with Engelmann, who paid Lindheimer for his plant collections. But sometimes, Lindheimer would add in the most interesting of comments, such as, “Dr. Koester’s medical treatments here are mostly unfortunate, often ghastly. Do let me know [through your contacts in] Frankfurt whether he is competent at all to practice even as a last resort.” [p. 117]

Texas Star (Lindheimera texana), growing wild

Sometimes Lindheimer’s descriptions of the Texas landscape were so poetic that I longed to have been a witness to the Texas that once was. In reference to the area that would become New Braunfels, Lindheimer wrote: “It is sufficient that we are at least here, where the streams flow crystal clear over the rocky beds. The fluid element gleams emerald green, and in its greater depths the fish rush back and forth visibly. Powerful springs cascade down from the rocky hills. They are probably subterranean brooks that have gathered in the caves of the limestone boulders and suddenly come to the surface. Forest, grazing land, and land for cultivated fields of the best quality are available. But what does that matter to me? Palmate yuccas, cactus, and mimosas and the fragrance and blossoms of them all, that’s for me. Here I have seen for the first time the total splendor of the prairies. Flower upon flower, richer than the richest Persian carpet….[p.112] If you are interested in Texas’ natural and cultural history, Goyne’s A Life Among the Texas Flora: Ferdinand Lindheimer’s Letters to George Engelmann is an excellent source of enlightenment.

When Prince Carl of Solms-Braunfels purchased Texas land for a German colony in 1844, Lindheimer served as a guide for the immigrants. He was deeded land in the new German settlement of New Braunfels and built his home on land overlooking the blue Comal River, and from there he continued his plant collecting, got married, and began his family. It is estimated that during his entire lifetime, Lindheimer collected between 80,000 and 100,000 specimens, many of which were discoveries of new species or sub-species.

Lindheimer was known for his mild voice but strong opinions. He was an active supporter of freedom and justice.

Lindheimer was known for his mild voice but strong opinions. He was an active supporter of freedom and justice.

As a botanist, he was respected by many Native Americans, and in fact the fierce Kiowa chief Santanta was a regular visitor to Lindheimer’s home. (Note: On the wall in the front room of Lindheimer’s home one can see the painting above of Chief Santana by Ralph Wall; it was added to the home in 1980.)

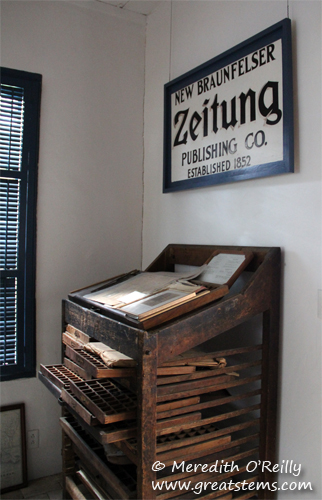

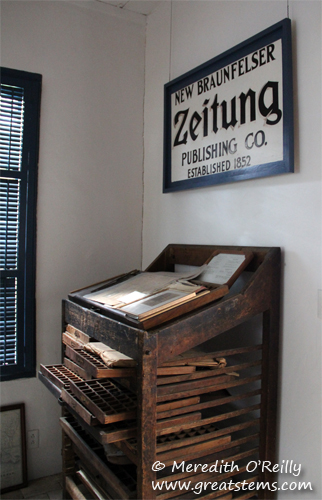

For 20 years, Lindheimer served as the first editor of the Neu-Braunfelser Zeitung, a bilingual German-English newspaper that lasted more than a century. He published the newspaper from his house and included his own sometimes controversial writings. He was involved in local education and served as the county’s first Justice of the Peace. After his retirement, Lindheimer returned to his passion for Texas plants, until his death on December 2, 1879.

For 20 years, Lindheimer served as the first editor of the Neu-Braunfelser Zeitung, a bilingual German-English newspaper that lasted more than a century. He published the newspaper from his house and included his own sometimes controversial writings. He was involved in local education and served as the county’s first Justice of the Peace. After his retirement, Lindheimer returned to his passion for Texas plants, until his death on December 2, 1879.

Today the Lindheimer Home is under the care of the New Braunfels Conservation Society. It has been restored to look much as it did during Lindheimer’s lifetime. John Turner, who gave us a tour of the Lindheimer home, was greatly involved in the restoration, which was completed in 1995.

Today the Lindheimer Home is under the care of the New Braunfels Conservation Society. It has been restored to look much as it did during Lindheimer’s lifetime. John Turner, who gave us a tour of the Lindheimer home, was greatly involved in the restoration, which was completed in 1995.

Stucco covers three sides of the main building, with the remaining surface exposing the fachwerk, or half-timbering, technique employed by German settlers, with rocks or brick filling space between the timbers.

Stucco covers three sides of the main building, with the remaining surface exposing the fachwerk, or half-timbering, technique employed by German settlers, with rocks or brick filling space between the timbers.

The house has a second-story loft, as well as a cellar, and a second building sits where the former outhouse had been.

The house has a second-story loft, as well as a cellar, and a second building sits where the former outhouse had been.

Inside, one sees much of the original furniture used by Lindheimer and his family.

Inside, one sees much of the original furniture used by Lindheimer and his family.

Original newspapers and plant specimens, as well as photographs and other items, are out on display. The image above is Lindheimer’s granddaughter Sida and her husband.

Original newspapers and plant specimens, as well as photographs and other items, are out on display. The image above is Lindheimer’s granddaughter Sida and her husband.

The Comal Master Gardeners do an exquisite job of maintaining pristine colorful gardens around the quaint Lindheimer house. The gardens are a combination of assorted Texas natives, popular favorites, and a selection of plants specifically named after Lindheimer.

The Comal Master Gardeners do an exquisite job of maintaining pristine colorful gardens around the quaint Lindheimer house. The gardens are a combination of assorted Texas natives, popular favorites, and a selection of plants specifically named after Lindheimer.

Lindheimer Morning Glory (Ipomoea lindheimeri)

Lindheimer Morning Glory (Ipomoea lindheimeri)

The most notable perhaps was the dainty but beautiful Lindheimer’s Morning Glory, freshly blooming just in time for my visit.

The Master Gardeners visiting with us said they hope to continue increasing the Lindheimer plants, especially those well suited for a garden (for not all of the Lindheimer plants would qualify as being ideal choices). After reading Lindheimer’s letters that accompanied his plant specimen shipments to Engelmann, I’d like to also suggest continuing to add native plant species that Lindheimer particularly loved collecting from the Texas wild – what fun it would be to research those! For it cannot be questioned that Lindheimer’s true passion was Texas flora, not just collecting it but experiencing adventure along the way.

The Master Gardeners visiting with us said they hope to continue increasing the Lindheimer plants, especially those well suited for a garden (for not all of the Lindheimer plants would qualify as being ideal choices). After reading Lindheimer’s letters that accompanied his plant specimen shipments to Engelmann, I’d like to also suggest continuing to add native plant species that Lindheimer particularly loved collecting from the Texas wild – what fun it would be to research those! For it cannot be questioned that Lindheimer’s true passion was Texas flora, not just collecting it but experiencing adventure along the way.

But the Lindheimer garden is truly charming, and I commend the Master Gardeners for their dedication to creating such a lovely setting that is both an array of color and a tribute to Lindheimer. It is a garden that is a pleasure to stroll through. In fact, I was so delighted with the Lindheimer Morning Glory that I made sure to purchase one for my own garden at the Wildflower Center plant sale soon thereafter.

Today, many plant species (and one snake) bear the name Lindheimer in their scientific name. Depending on the source, there are at least 30 such species and possibly more than 40, but with taxonomic changes happening all the time, there is no way for me to confirm an accurate number. But after touring the Lindheimer Home and gardens and knowing that I intended to write this article, I decided to increase my personal collection of plants named for Lindheimer, and so far I am up to at least 7 (there might be others on the property):

Today, many plant species (and one snake) bear the name Lindheimer in their scientific name. Depending on the source, there are at least 30 such species and possibly more than 40, but with taxonomic changes happening all the time, there is no way for me to confirm an accurate number. But after touring the Lindheimer Home and gardens and knowing that I intended to write this article, I decided to increase my personal collection of plants named for Lindheimer, and so far I am up to at least 7 (there might be others on the property):

· Silk Tassel (Garrya ovata ssp. lindheimeri)

· Lindheimer’s Senna (Senna lindheimeriana)

· Big Muhly (Muhlenbergia lindheimeri)

· Lindheimer’s Morning Glory (Ipomoea lindheimeri)

· Lindheimer’s Beebalm (Monarda lindheimeri)

· Texas Star (Lindheimera texana)

· Devil’s Shoestring (Nolina lindheimeriana)

I’m technically not counting Evergreen Sumac (Rhus virens Lindheimer ex Gray), but some people do — in any case, I have it. With luck, someday I’ll be growing again White Gaura (Gaura lindheimeri), which succumbed to drought, and perhaps I’ll be able to add Balsam Gourd (Ibervillea lindheimeri), Woolly Ironweed (Vernonia lindheimeri), and others to the list.

Thank you to John Turner of the New Braunfels Conservation Society and to the Comal Master Gardeners for sharing a moment in time with Lindheimer with me. The friendliness of my tour guides, my love of Texas botany, and my being a former resident of New Braunfels made my visit just like coming home. Plus I had a great time speaking to the 2012 Master Gardener class. On the way home, I viewed wildflowers in the Texas Hill Country. What a great day!

Thank you to John Turner of the New Braunfels Conservation Society and to the Comal Master Gardeners for sharing a moment in time with Lindheimer with me. The friendliness of my tour guides, my love of Texas botany, and my being a former resident of New Braunfels made my visit just like coming home. Plus I had a great time speaking to the 2012 Master Gardener class. On the way home, I viewed wildflowers in the Texas Hill Country. What a great day!

Note: If you are wanting to visit the Lindheimer Home, you’ll need to contact New Braunfels Conservation Society in advance to arrange a tour. In fact, I hear that the entire NBCS Conservation Plaza is a must-see, and it is a must-see I must see on my next visit!

You can also see how big the pollen sacs are on this little honeybee.

You can also see how big the pollen sacs are on this little honeybee.

And so it grows, does my Buffalo Grass patch. With luck, the female inflorescences will appear soon, and soon thereafter, so will seeds. Lucky for me, Buffalo Grass also spreads by stolons, or above-ground runners — where the plant touches the ground, it can take root. Sometimes Buffalo Grass roots can reach 5-6 feet into the ground, but most will be closer to the surface of the soil. I suspect my Buffalo Grass patch has relied on a lot on spreading by stolons — this is just fine with me. It can do so right up near my garden beds, too — it won’t be hard to keep it out of the beds. Not like Bermuda, the grass of nightmares.

And so it grows, does my Buffalo Grass patch. With luck, the female inflorescences will appear soon, and soon thereafter, so will seeds. Lucky for me, Buffalo Grass also spreads by stolons, or above-ground runners — where the plant touches the ground, it can take root. Sometimes Buffalo Grass roots can reach 5-6 feet into the ground, but most will be closer to the surface of the soil. I suspect my Buffalo Grass patch has relied on a lot on spreading by stolons — this is just fine with me. It can do so right up near my garden beds, too — it won’t be hard to keep it out of the beds. Not like Bermuda, the grass of nightmares.

American Smoke Tree

American Smoke Tree

Goldenrods have high wildlife value. They are extremely important to pollinators, offering copious nectar and large, sticky pollen grains. At any point in the warmth of the day, I have hundreds of pollinators visiting the blooms. Standing up close to the flowers, I enjoy the movement of flying insects all around me, bees and wasps completely ignoring me as I turn blooms here and there for a picture or to study a particular insect. They just go about their business, eagerly moving from bloom to bloom to bloom. One cool morning, I even found three honeybees effectively frozen on the Goldenrod flowers, waiting to be warmed by the sun so they could begin to collect pollen again.

Goldenrods have high wildlife value. They are extremely important to pollinators, offering copious nectar and large, sticky pollen grains. At any point in the warmth of the day, I have hundreds of pollinators visiting the blooms. Standing up close to the flowers, I enjoy the movement of flying insects all around me, bees and wasps completely ignoring me as I turn blooms here and there for a picture or to study a particular insect. They just go about their business, eagerly moving from bloom to bloom to bloom. One cool morning, I even found three honeybees effectively frozen on the Goldenrod flowers, waiting to be warmed by the sun so they could begin to collect pollen again.

Lady beetles, mating

Lady beetles, mating

Ferdinand Jacob Lindheimer was born on May 21, 1802 (some sources say 1801), in Frankfurt, Germany. Immigrating to the United States in 1834 during a time of political unrest in Germany, Lindheimer traveled first to Illinois and then to Mexico by way of New Orleans. For a short while, he worked on a couple of plantations in Mexico, collecting plants and insects in his spare time. Upon hearing about the Texas Revolution, however, he returned north to enlist in the army, missing the Battle of San Jacinto by a day. After completing his time in the army, Lindheimer farmed for a short while in the Houston area, all the while studying Texas plants and insects.

Ferdinand Jacob Lindheimer was born on May 21, 1802 (some sources say 1801), in Frankfurt, Germany. Immigrating to the United States in 1834 during a time of political unrest in Germany, Lindheimer traveled first to Illinois and then to Mexico by way of New Orleans. For a short while, he worked on a couple of plantations in Mexico, collecting plants and insects in his spare time. Upon hearing about the Texas Revolution, however, he returned north to enlist in the army, missing the Battle of San Jacinto by a day. After completing his time in the army, Lindheimer farmed for a short while in the Houston area, all the while studying Texas plants and insects.

Through Lindheimer’s letters, we learn of his fondness for sweet native grapes and how pecans and persimmons were regular food sources. We learn of different wildlife he encountered, his attention to physical fitness and health, his understanding of local Native American tribes, and just how many species of cacti and yucca there really are in Texas.

Through Lindheimer’s letters, we learn of his fondness for sweet native grapes and how pecans and persimmons were regular food sources. We learn of different wildlife he encountered, his attention to physical fitness and health, his understanding of local Native American tribes, and just how many species of cacti and yucca there really are in Texas.

Lindheimer was known for his mild voice but strong opinions. He was an active supporter of freedom and justice.

Lindheimer was known for his mild voice but strong opinions. He was an active supporter of freedom and justice.  For 20 years, Lindheimer served as the first editor of the Neu-Braunfelser Zeitung, a bilingual German-English newspaper that lasted more than a century. He published the newspaper from his house and included his own sometimes controversial writings. He was involved in local education and served as the county’s first Justice of the Peace. After his retirement, Lindheimer returned to his passion for Texas plants, until his death on December 2, 1879.

For 20 years, Lindheimer served as the first editor of the Neu-Braunfelser Zeitung, a bilingual German-English newspaper that lasted more than a century. He published the newspaper from his house and included his own sometimes controversial writings. He was involved in local education and served as the county’s first Justice of the Peace. After his retirement, Lindheimer returned to his passion for Texas plants, until his death on December 2, 1879. Today the Lindheimer Home is under the care of the

Today the Lindheimer Home is under the care of the

Stucco covers three sides of the main building, with the remaining surface exposing the fachwerk, or half-timbering, technique employed by German settlers, with rocks or brick filling space between the timbers.

Stucco covers three sides of the main building, with the remaining surface exposing the fachwerk, or half-timbering, technique employed by German settlers, with rocks or brick filling space between the timbers.  The house has a second-story loft, as well as a cellar, and a second building sits where the former outhouse had been.

The house has a second-story loft, as well as a cellar, and a second building sits where the former outhouse had been.  Inside, one sees much of the original furniture used by Lindheimer and his family.

Inside, one sees much of the original furniture used by Lindheimer and his family.  Original newspapers and plant specimens, as well as photographs and other items, are out on display. The image above is Lindheimer’s granddaughter Sida and her husband.

Original newspapers and plant specimens, as well as photographs and other items, are out on display. The image above is Lindheimer’s granddaughter Sida and her husband.

The

The  Lindheimer Morning Glory (Ipomoea lindheimeri)

Lindheimer Morning Glory (Ipomoea lindheimeri) The Master Gardeners visiting with us said they hope to continue increasing the Lindheimer plants, especially those well suited for a garden (for not all of the Lindheimer plants would qualify as being ideal choices). After reading Lindheimer’s letters that accompanied his plant specimen shipments to Engelmann, I’d like to also suggest continuing to add native plant species that Lindheimer particularly loved collecting from the Texas wild – what fun it would be to research those! For it cannot be questioned that Lindheimer’s true passion was Texas flora, not just collecting it but experiencing adventure along the way.

The Master Gardeners visiting with us said they hope to continue increasing the Lindheimer plants, especially those well suited for a garden (for not all of the Lindheimer plants would qualify as being ideal choices). After reading Lindheimer’s letters that accompanied his plant specimen shipments to Engelmann, I’d like to also suggest continuing to add native plant species that Lindheimer particularly loved collecting from the Texas wild – what fun it would be to research those! For it cannot be questioned that Lindheimer’s true passion was Texas flora, not just collecting it but experiencing adventure along the way.  Today, many plant species (and one snake) bear the name Lindheimer in their scientific name. Depending on the source, there are at least 30 such species and possibly more than 40, but with taxonomic changes happening all the time, there is no way for me to confirm an accurate number. But after touring the Lindheimer Home and gardens and knowing that I intended to write this article, I decided to increase my personal collection of plants named for Lindheimer, and so far I am up to at least 7 (there might be others on the property):

Today, many plant species (and one snake) bear the name Lindheimer in their scientific name. Depending on the source, there are at least 30 such species and possibly more than 40, but with taxonomic changes happening all the time, there is no way for me to confirm an accurate number. But after touring the Lindheimer Home and gardens and knowing that I intended to write this article, I decided to increase my personal collection of plants named for Lindheimer, and so far I am up to at least 7 (there might be others on the property):  Thank you to John Turner of the New Braunfels Conservation Society and to the Comal Master Gardeners for sharing a moment in time with Lindheimer with me. The friendliness of my tour guides, my love of Texas botany, and my being a former resident of New Braunfels made my visit just like coming home. Plus I had a great time speaking to the 2012 Master Gardener class. On the way home, I viewed wildflowers in the Texas Hill Country. What a great day!

Thank you to John Turner of the New Braunfels Conservation Society and to the Comal Master Gardeners for sharing a moment in time with Lindheimer with me. The friendliness of my tour guides, my love of Texas botany, and my being a former resident of New Braunfels made my visit just like coming home. Plus I had a great time speaking to the 2012 Master Gardener class. On the way home, I viewed wildflowers in the Texas Hill Country. What a great day!

Prairie Fleabane

Prairie Fleabane

The soft pink puffballs are a contrast to the sneaky thorns up and down the branches.

The soft pink puffballs are a contrast to the sneaky thorns up and down the branches.

2-4-6-8, Pom-Poms I appreciate!

2-4-6-8, Pom-Poms I appreciate!

What about the Blackfoot Daisies, twice as big as when I planted them before our trip?

What about the Blackfoot Daisies, twice as big as when I planted them before our trip?

As we were getting ready to leave, my husband called me over to see a creature hanging upside-down from the car of a volunteer. It turned out to be a gorgeous Lepidopteran.

As we were getting ready to leave, my husband called me over to see a creature hanging upside-down from the car of a volunteer. It turned out to be a gorgeous Lepidopteran.

Polyphemus moths have an average wing span of about 6 inches. As adults, they also have reduced mouth parts, meaning that they can’t eat, so they have one job to focus on: reproduction. The feathery antennae of the males are used to detect the scent of unmated females. Whether the antennae also make the male moths look sexy to females, I cannot attest. But for this female, I think they look pretty cool. Not getting to eat means something else — the moths have a short lifespan of less than a week.

Polyphemus moths have an average wing span of about 6 inches. As adults, they also have reduced mouth parts, meaning that they can’t eat, so they have one job to focus on: reproduction. The feathery antennae of the males are used to detect the scent of unmated females. Whether the antennae also make the male moths look sexy to females, I cannot attest. But for this female, I think they look pretty cool. Not getting to eat means something else — the moths have a short lifespan of less than a week. Perhaps because it was darker in the car, the moth came to life once we got moving on the road. By the time we were on the highway, it was fluttering all about, making for quite an interesting drive home. At one point, the Polyphemus moth decorated my husband as a bowtie.

Perhaps because it was darker in the car, the moth came to life once we got moving on the road. By the time we were on the highway, it was fluttering all about, making for quite an interesting drive home. At one point, the Polyphemus moth decorated my husband as a bowtie.

While I was out there admiring our happy little bloomer, I noticed this black-and-white Lepidopteran.

While I was out there admiring our happy little bloomer, I noticed this black-and-white Lepidopteran.